SDG 10 – “Reduce inequalities within and among countries” – is made up of 10 targets and 11 indicators. SDG 10 will be reviewed at the High-Level Political Forum in 2019, along with SDGs 4, 8, 13, and 16. SDG 17 is reviewed annually.

SDG 10’s targets reflect the idea that inequality is a multidimensional issue, often made up of economic (10.1, 10.2, 10.5, 10.a, 10.b, 10.c), social (10.3, 10.7), and political (10.4, 10.6) factors. SDG 10 also reflects an understanding of inequality as more complex than just an “inequality of outcomes” (disparities in living conditions) but also an “inequality of opportunities” (disparities in access to education, work, or political participation).1 Furthermore, it acknowledges that inequalities are experienced by all countries, not just developing ones.

Context

The Millennium Development Goals did not address inequality. One of its major critiques was that it in fact masked, if not exacerbated, inequalities.2 Thus the SDGs, especially SDG 10, represents a significant shift in the global conversation on development.

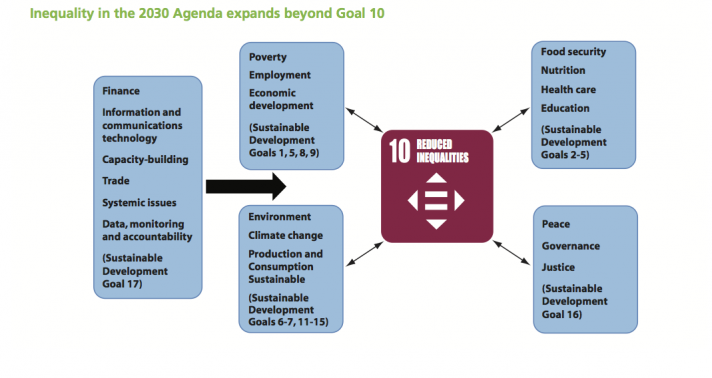

SDG 10 is a standalone goal on inequality that sits in the context of the 2030 Agenda, which relies on addressing inequalities to ensure that all its goals and targets are met for all segments of society. The 2030 Agenda includes other standalone goals (eg SDG 5 Gender Equality) and individual targets that address inequality. Examples include targets on social protection systems for all (1.3), access by all people to food (2.1), universal health coverage (3.8), completion of primary and secondary education by all girls and boys (4.1), and universal access to drinking water (6.1). Yet, while inequality is interwoven into the SDGs, SDG 10 covers more of the systemic (all targets) and financial (SDGs 10.A, 10.B and 10.C) means of reducing inequality. Thus, it is important for institutions to address not only the inequalities embedded in the SDGs they are prioritizing, but also SDG 10 as a standalone goal.

In fact, the success of the 2030 Agenda relies on taking steps to achieve SDG 10, both within and between countries.3 There is a growing sense that inclusive development requires not only addressing poverty, but also inequalities. Not only can inequality be a serious threat to social and political stability, it can also threaten sustained growth.[ref]Carpentier, Chantal Line, Richard Kozul-Wright, Fabio David Passos. 2015. Goal 10: Why addressing inequality matters. https://unchronicle.un.org/article/goal-10-why-addressing-inequality-matters. Accessed August 21, 2018.[/ref] It negatively impacts the effectiveness of poverty reduction actions by excluding large groups of people from their positive impacts.4 It also negatively impacts the environment, often with a disproportionate impact on the poor and marginalized, whose livelihoods, rights, and culture are frequently closely connected to the environment.5

Small-scale fisheries, which happen all along the Mekong, are an example of one of the livelihoods that can be impacted by changes to the environment. Photo by BigBrotherMouse, Wikimedia. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Thus, despite global growth, inequalities have risen.6 Yet, addressing economic issues alone is not enough. Disparities in income and wealth are to a large extent the result of inequalities in opportunities, such as access to quality services for education and health.7 Other interventions, such as supporting essential public programs in healthcare and education, with multi-sectoral and multi-stakeholder involvement, are necessary components of reducing inequalities.8 In addition, ensuring that economic gains means benefits for all requires policies and programs to take into account those who are most in need.9 Furthermore, changes cannot only be made in-country. Cooperation between countries is needed to ensure that those countries that are lagging behind can take advantage of regional opportunities.10

from UNESCAP. 2018. Inequality in Asia and the Pacific in the era of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Accessed August 21, 2018.

Regionalisation and Localisation

Reducing inequalities, inclusive development, and sustainable growth are frequently used to describe the direction of development in the LMCs, especially the least developed countries of this group, Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar. However, the reality is that while reducing inequalities is intended to underpin policies in these countries, implementation of SDG 10 is lagging significantly.

One of the more underdeveloped goals, most of the SDG 10 targets lack a methodology, let alone data. This limits the ability of countries to understand their baseline, and hampers accountability. In addition, implementation of SDG 10, while recognized as needing more work by both ASEAN11 and UNESCAP12, seems to be taking a back-seat for both sub-regional and regional cooperation.

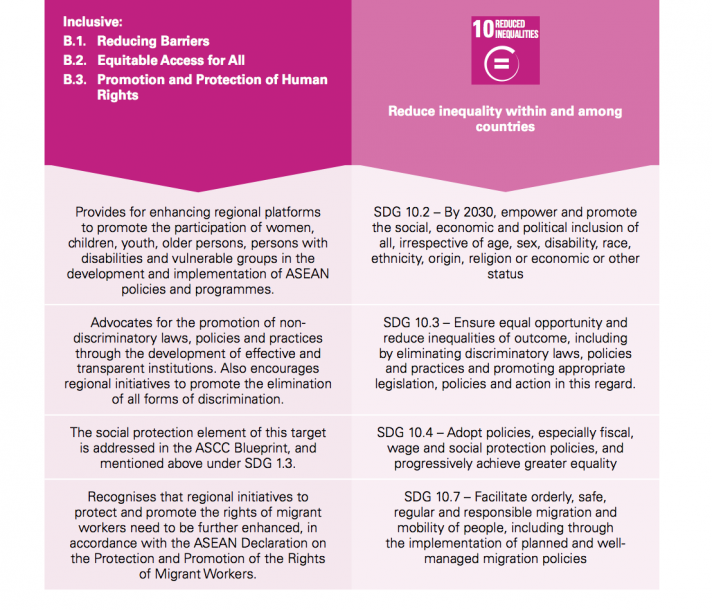

For example, the ASEAN Vision notes that like the SDGs, it is based on the principle of inclusivity – leaving no one behind.13 ASEAN indicates that this means “reducing barriers to disadvantaged groups, ensuring equitable access for all, and promotion of human rights.”14 In addition, ASEAN has repeatedly stated its commitment to addressing inequality through mutual assistance and cooperation.15 Yet, in the ASCC Blueprint 2025, there is high-level, non-comprehensive overlap for only four of the 10 SDG 10 targets.

On the left is the ASCC Blueprint; on the right is the SDGs that correlate. From ASEAN. October 2017. Voices: Bulletin of the ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community. Accessed August 21, 2018

Similarly, ESCAP’s efforts to promote the reduction of inequalities remains limited in respect of SDG 10. ESCAP has identified priorities for reducing inequalities, which include:

- Strengthening social protection;

- Prioritizing education;

- Protecting the poor and disadvantaged from disproportionate impact of environmental hazards;

- Addressing the digital divide and ICT infrastructure;

- Addressing persistent inequalities in technological capabilities among and within countries;

- Increasing effectiveness of fiscal policies;

- Improving data collection to identify and address inequality; and

- Deepening regional cooperation.16

While strengthening social protection (SDG 10.4), increasing effectiveness of fiscal policies (SDG 10.4), improving data collection, and deepening regional cooperation have the potential to impact implementation of SDG 10, there are other notable gaps, such as with regard to migration (SDG 10.7).

ESCAP, in its regional roadmap for implementing the SDGs, has noted that areas for regional cooperation include promoting analytical studies and policy advocacy to address inequalities, as well as other related to gender equality and women’s empowerment, addressing employment issues, dealing with population aging, and implementing strategies to assist people with disabilities. Managing migration is also one of the actions noted by ESCAP in this document.17

Population aging is one of the priority areas for addressing inequalities. Photo by Peter van der Sluijs, Wikimedia. Licensed under GNU Free Documentation License.

What this suggests is that while tackling inequality generally is understood as key to implementing the SDGs, implementation of SDG 10 itself lacks the intergovernmental coordination necessary to reduce inequalities not only within countries, but between countries as well. More work, specifically targeting SDG 10, is needed.

Means of Implementation

As mentioned above, SDG 10 generally focuses on the means of implementation for reducing inequality. However, the goal also features three specific means of implementation targets – SDG 10.A (implement the principle of special and differential treatment for developing countries, in particular least developed countries, in accordance with WTO agreements), 10.B (Encourage ODA and financial flows, including foreign direct investment, to states where the need is greatest, in particular LDCs, African countries, SIDS, and LLDCs, in accordance with their national plans and programs), and 10.C (By 2030, reduce to less than 3% the transaction costs of migrant remittances and eliminate remittance corridors with costs higher than 5%).

Migrant labourers work in areas as diverse as construction and childcare. Photo by ILO/Emmanuel Maillard, Flickr. Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

All of the LMCs are members of the WTO, and with three of the five LMCs being least developed countries, SDG 10.A has particular significance. “Special and differential treatment” is a special provision in WTO agreements that gives developing countries preferential treatment, for instance giving them more time to meet commitments, or providing measures to increase trading opportunities.18 This is one way to support less economically developed countries to reap the benefits of others that are more well off, perhaps in their region.

SDG 10.B is also notable, and not just because it impacts Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar as least developed countries. Encouraging financial flows, especially foreign direct investment, is important, and is one of the pillars of the 2002 Monterrey Consensus on financing for sustainable development. Recently, in the Addis Ababa Action Agenda, UN member states committed to overhaul financial practices, in order to further the 2030 Agenda. However, foreign direct investment is commonly concentrated in certain sectors, and can bypass countries most in need. 19 For the LMCs, Vietnam received the highest net total foreign direct investment inflows in 2015. As compared to other ASEAN countries, only Indonesia and Singapore received more. Lao PDR received the lowest in the LMCs. As compared to other ASEAN countries, only Brunei received less.

The FDI is on a net basis, and computed as follows: Net FDI = Equity + Net Inter-company Loans + Reinvested Earnings. The net basis concept implies that the followings should be deducted from the FDI gross flows: (1) reverse investment (made by a foreign affiliate in a host country to its parent company/direct investor; (2) loans given by a foreign affiliate to its parent company; and (3) repayments of intra-company loan (paid by a foreign affiliate to its parent company). As such, FDI net inflows can be negative.20

Country Total net inflow USD (2015)

Brunei Darussalam 171.31603467216

Cambodia 1700.9686020738

Indonesia 16916.78701596

Lao PDR 1079.1541578733

Malaysia 11289.603723398

Myanmar 2824.478

Philippines 5724.2156041938

Singapore 61284.8

Thailand 8027.4855578723

Vietnam 11800

Official development assistance (ODA) is another crucial resource for developing countries, contributing greatly to the economies of the LMCs. However, reviewing ODA on SDG 10 shows a bleak picture. Globally, less than 1% of foundation giving and ODA from 2016 on was focused on SDG 10.21 As SDG 10.B refers to financing on the basis of national plans and priorities, the numbers suggest that national plans and programs do not prioritize SDG 10, which will in turn hamper the implementation of the SDGs as a whole. While these numbers are not from official UNSD SDG data, it provides a starting point for where SDG 10 stands in terms of importance. Ultimately, very little attention has been paid to funding SDG 10.

Remittances, the focus of SDG 10.C.1, are amounts of money sent by migrant workers to their families in their home countries and a significant source of income for many. Although small on an individual scale, globally in 2016 the amount sent was triple the amount of total official development assistance. For individual families, the amounts can effectively improve the living standards of both the migrant workers and their families back home. Reducing the cost of sending remittances frees up more disposable income for remittance-receiving families.22 SDG 10.C.1 has two parts, and there is data available on the first, which is to reduce remittance costs to 3% of the remittance. In 2017, the costs in Lao PDR were the highest in the LMCs, at 16%, while Vietnam’s were the lowest, at just under 8%.

Follow up and review, monitoring and evaluation

SDG 10 is one of the most data-poor SDGs.23 Very few of the SDG 10 indicators are developed. Seven of the 11 remain at Tier III, which means that they are not methodologically developed and do not have data. The methodology for SDG 10.c.1 and part of 10.b.1 is developed, but these indicators lack data. Data is produced by at least 50% of the countries globally for the remaining indicators (SDGs 10.6.1, 10.a.1 and part of 10.b.1).

Indicator Tier Custodian Agency Notes

10.1.1 III World Bank No work plan was made available for this indicator

10.2.1 III World Bank The World Bank is working on producing a baseline set of statistics.

10.3.1 III OHCHR Same as 16.b.1. It is expected that methodological work on this indicator be completed towards the end ot 2018.

10.4.1 III ILO No work plan was made available for this indicator

10.5.1 III IMF No

10.6.1 I DESA/FFDO Same as 16.8.1

10.7.1 III ILO, World Bank The methodological work was expected to be completed by 2016.

10.7.2 III DESA Population Division, IOM Methological work was completed in 2017. Data is being collected for a larger group of countries.

10.a.1 I ITC, UNCTAD, WTO --

10.b.1 I (ODA) - II (FDI) OECD --

10.c.1 II World Bank --

The data landscape for the LMCs mirrors that of other countries, meaning that it is limited. Data for all the LMCs are available only for indicators 10.6.1, 10.b.1, and 10.c.1. For Indicator 10.1.1, data are available only for Laos, Thailand and Vietnam. Data are not available for any of the other indicators.

There are 11 different relevant international organizations globally, but only the six represented above are relevant for the LMCs.24

SDG 10.B.1 data can be disaggregated by type of flow (ODA, OOF, private), by donor, recipient country, type of finance, and type of aid.25

Although more methodological work is needed, some critiques have already arisen. For example, one critique is that SDGs 10.1.1 and 10.2.1 use an empirical measure (Growth rates of household expenditure or income per capita among the bottom 40 percent of the population and the total population; proportion of people living below 50% of the median income) rather than a measure of economic inequality, like the Palma Ratio or the Gini Coefficient. For SDG 10.1, this means that it leaves out any mention of the top end of the income spectrum and the role that they may play in shifting inequality. For SDG 10.2, two different types of household surveys, income and consumption, are used as data sources, which means that cross-country comparisons of inequality require some caution.26 However, there are also critiques on indicators with already-developed methodologies. For instance, SDGs 10.6.1 and 10.A.1 rely on the term, “developing countries”, but there is no established convention for designating a country “developing” or “developed”.27 Thus for these indicators, it is important to review the definitions used to fully understand the data.

References

- 1. Sieler, Simone. 2016. SDG 10: Reducing inequalities – Concepts and approaches for development cooperation. https://www.kfw-entwicklungsbank.de/PDF/Download-Center/PDF-Dokumente-Development-Research/2016-05-12-EK_Inequalities_EN.pdf. Accessed August 20, 2018.

- 2. Donald, Kate. 2016. II.10: Will inequality get left behind in the 2030 Agenda? https://www.2030spotlight.org/en/book/605/chapter/ii10-will-inequality-get-left-behind-2030-agenda. Accessed August 21, 2018.

- 3. Donald, Kate. 2016. II.10: Will inequality get left behind in the 2030 Agenda? https://www.2030spotlight.org/en/book/605/chapter/ii10-will-inequality-get-left-behind-2030-agenda. Accessed August 21, 2018.

- 4. UNESCAP. 2018. Inequality in Asia and the Pacific in the era of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/publications/ThemeStudyOnInequality.pdf. Accessed August 21, 2018.

- 5. UNESCAP. 2018. Inequality in Asia and the Pacific in the era of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/publications/ThemeStudyOnInequality.pdf. Accessed August 21, 2018.

- 6. UNCTAD. 2013. Growth and Poverty Eradication: Why addressing inequality matters. http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/presspb2013d4_en.pdf. Accessed August 20, 2018.

- 7. UNESCAP. 2017. Sustainable Social Development in Asia and the Pacific: Towards a People-Centred Transformation. https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/publications/Sustainable%20Social%20Development%20in%20A-P.pdf. Accessed August 21, 2018.

- 8. UNESCAP. 2018. Inequality in Asia and the Pacific in the era of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/publications/ThemeStudyOnInequality.pdf. Accessed August 21, 2018.

- 9. UNESCAP. 2017. Sustainable Social Development in Asia and the Pacific: Towards a People-Centred Transformation. https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/publications/Sustainable%20Social%20Development%20in%20A-P.pdf. Accessed August 21, 2018.

- 10. UNESCAP. 2017. Eradicating poverty and promoting prosperity in a Changing Asia-Pacific. Accessed August 21, 2018.

- 11. UNESCAP. 2017. ASEAN SDG Baseline. Accessed August 23, 2018.

- 12. UNESCAP. 2018. Asia and the Pacific SDG Progress Report 2017. Accessed August 21, 2018.

- 13. UN. 2017. Complementarities between the ASEAN Community Vision 2025 and the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: A Framework for Action. Accessed August 21, 2018.

- 14. UN. 2017. Complementarities between the ASEAN Community Vision 2025 and the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: A Framework for Action. Accessed August 21, 2018.

- 15. ASEAN. October 2017. Voices: Bulletin of the ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community. http://asean.org/storage/2017/10/VOICES_Addressing-Poverty-and-Inequality.pdf. Accessed August 21, 2018.

- 16. UNESCAP. 2018. Inequality in Asia and the Pacific in the era of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/publications/ThemeStudyOnInequality.pdf. Accessed August 21, 2018.

- 17. UNESCAP. 2017. Regional roadmap for implementing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in Asia and the Pacific. Accessed August 21, 2019.

- 18. WTO. Briefing Notes: Special and differential treatment. https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dda_e/status_e/sdt_e.htm. Accessed August 22, 2018.

- 19. UNCTAD. 2016. Target 10.b: ODA and FDI. http://stats.unctad.org/Dgff2016/prosperity/goal10/target_10_b.html. Accessed August 20, 2018.

- 20. Foreign direct investment net inflows, intra- and extra-ASEAN. Accessed January 24, 2019.

- 21. SDG Funders. Sustainable Development Goals – Reduced Inequalities. http://sdgfunders.org/sdgs/dataset/recent/goal/reduced-inequalities/. Accessed August 20, 2018.

- 22. International Fund for Agricultural Development. 2017. Sending money home: Contributing to the SDGs, one family at a time. https://www.ifad.org/documents/38714170/39135645/Sending+Money+Home+-+Contributing+to+the+SDGs%2C+one+family+at+a+time.pdf/c207b5f1-9fef-4877-9315-75463fccfaa7. Accessed August 23, 2018.

- 23. UNESCAP. 2018. Asia and the Pacific SDG Progress Report 2017. Accessed August 21, 2018.

- 24. Financing for development office, DESA. Metadata: 10.6.1. Accessed August 23, 2018.

- 25. OECD. Metadata: SDG 10.B.1. Accessed August 23, 2018.

- 26. UNCTAD. 2016. Target 10.2: Social, economic and political inclusion. http://stats.unctad.org/Dgff2016/prosperity/goal10/target_10_2.html. Accessed August 20, 2018.

- 27. UN Economic and Social Council. 2018. Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals: Report of the Secretary-General, Supplementary Information. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/files/report/2018/secretary-general-sdg-report-2018–Statistical-Annex.pdf. Accessed August 20, 2018.