Agrarian or small-scale, household-based farming and ‘artisanal fishing’ characterized by its small scale and low technology, have been the cornerstones of the region’s largely rural economies for many centuries. That is now changing. As policy, the Lower Mekong countries are shifting toward industrialized agriculture with a focus on commercial cash crops for export. Even so, the populations remain largely rural and the rice and fish production of small-holders continues to contribute significantly to local economies, not to mention household and community food security.

Mekong River fishing. Photo by Christine Andrada, Flickr, taken 29 October 2008. Licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Key crops

Rice dominates production, at both commercial and household levels. The Lower Mekong countries produced more than 109 million tons of paddy rice in 2017,1 with Vietnam, Thailand and Myanmar being the 5th, 6th and 7th largest producers in the world.2 While a large percentage of this rice goes to local trade and remains within the countries, the region is also a significant exporter of rice to the world. Thailand and Vietnam export the 2nd and 3rd largest volumes of rice, and Cambodia is the 8th largest exporter.3

Other important export crops include corn (maize), sugar, soy beans, cassava, coffee and natural rubber. Thailand was the world’s biggest natural rubber producer in 2017, its 4.4 million tonnes accounting for 33 percent of global production.4 In recent years rubber has expanded significantly in both Laos and Cambodia, with major investment by Vietnamese companies in southern Laos and Cambodia, and Chinese investment in northern Laos and Myanmar. After Thailand and Indonesia, Vietnam is the world’s third-largest producer. However, the market price of rubber has fallen by more than half from a high of $3.50 per kg in 20105 and this has had a large impact on earnings.

While coffee exports from number one global producer, Brazil, have been declining in recent years, Vietnam’s coffee exports have increased more than 9 percent between 2011 and 2015. Vietnam is second only to Brazil for coffee exports; also an important product in Laos, where it is the fifth largest export, though on a much smaller scale than Vietnam.6

Fisheries and aquaculture

The Mekong system is second only to the Amazon River in its biodiversity and it supports the world’s largest inland fishery. The people who live along its banks and within reach of its rich fisheries depend on it as a food source. Fish is estimated to supply 75% of people’s protein in some areas.7 The Mekong River Commission estimated in 2015 that 4.4 million tons of aquatic products come from capture fisheries and aquaculture,8 worth up to an estimated $17 billion a year,9 making up about 2.4 percent of the GDP of Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos and Thailand.

The region also has access to significant ocean fisheries in the Andaman Sea, Gulf of Thailand, and South China Sea. Thailand and Vietnam were the number three and four top global exporters of fish and fishery products respectively, based on value.10 Thailand is also a significant importer of seafood.11

Changing practices

The intensification of agriculture and fishing includes a push toward larger holdings, mechanized farming, large-scale commercial fishing and fisheries, increased regulation, and the transfer of land and resource rights to companies through both sales and expropriation. While these practices generally support increased production for export, they also tend to disadvantage small holders, as they have in other parts of the world. A number of aid programs are aimed at helping small-scale farmers and fishers adapt their practices to a market economy.

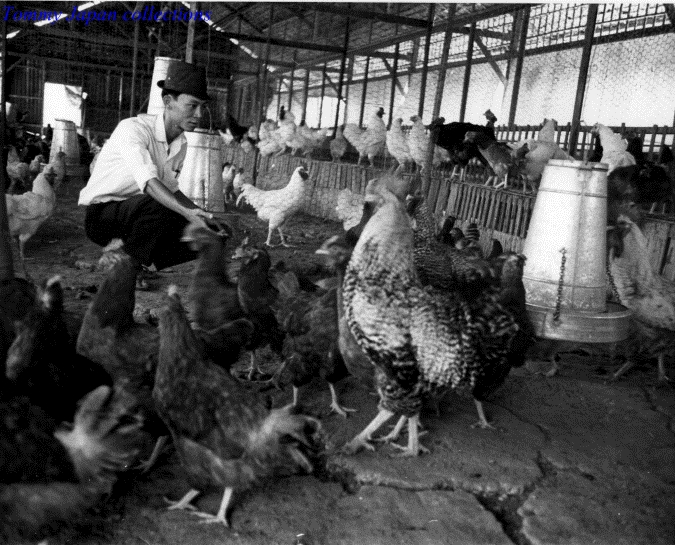

With his 31 year-old brother Tran Ngoc An, this progressive farmer, Tran Ngoc Diep 30 (above), operates a six-hectare farm in An Giang’s My Thoi village that has been so successful that other farmers come to study its methods. Photograph VA036048, No Date, William Foulke Collection, The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed 19 March 2015. Licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

The region has seen a trend towards value-added processing for agricultural and fish products, rather than selling raw materials. Thailand and Vietnam have been doing this for many years, especially with fermented and dried fish for use in the manufacture of products such as sauces and pastes. The listed Thai company Charoen Pokphand Foods (also known as CP) is one of the top agro-food companies in Asia-Pacific and an example of companies processing and adding value to products in the region.12

Pesticides and other chemicals

The effects of increased use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers in intensive farming of crops and aquaculture do not appear to have been systematically measured in the region. However, widespread use of a variety of chemicals, including ones banned in other parts of the world, has been recognized in many reports, along with the observation that chemicals tend to be handled improperly and few to no precautions taken with their use. The fact that labeling and instructions are often in languages other than native ones, particularly in Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar, further exacerbates the situation.

With the exception of Myanmar, all Lower Mekong countries have approved the Rotterdam Convention on the trade and use of pesticides internationally,13 and have government representation for reporting and information sharing. Nonetheless, both pesticide and chemical fertilizer use are known to be high, as farmers often increase their use to try to maximize production. A number of aid agencies, such as FAO, as well as national extension services and academic institutions promote Integrated Pest Management and organic farming to curb the harmful use of chemicals across the region, particularly among small-scale farmers.

Sustainability

A child looks over a pump irrigating a rice field in Cambodia. Photo by Asian Development Bank, Flickr, taken 15 February 2011. Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Population pressures are also putting strain on agrarian systems. Like other parts of Asia, agriculture continues to be characterized by smallholder farmers cultivating less than two hectares, and mostly dependent on household members for labor.14 Data on average smallholder farm size is difficult to find15, however, increasing family size and the sale or transfer of land to larger holdings, are both reducing the average size of smallholders’ land.

Agrarian communities are also losing access to forests and fallow fields, which have traditionally provided grazing areas for livestock and supplementary foods, such as wild herbs, fruits, honey, mushrooms, and even insects, and in some cases provided cash incomes, as in the case of resin collection.16 Also when farmers can no longer afford to leave their fields fallow on a rotational basis, this puts strain on soils and tends to decrease productivity. All of these trends may negatively affect the food security of some households.

The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) started an Asia/Pacific regional initiative to support the UN’s Zero Hunger Challenge. Laos and Myanmar were among the first countries involved, but the program has been expanded to include all Lower Mekong countries.17 In January 2016, at a workshop involving national Ministries of Agriculture, Ministries of Health and FAO Representatives, three main thematic components were adopted for 2016-2017:

- Formulate food security and nutrition strategy, policy and coordination mechanisms

- Promote nutrition-sensitive agriculture

- Conduct data analysis and monitoring of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for decision-making.

The FAO’s initiative directly contributes to achieving SDG 2, the eradication of hunger by 2030.

Programs by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) and the UN have stated aims of addressing both food security and extreme poverty.18 Even so, agricultural policies in the region sometimes conflict, depending on whether they are being driven by concerns for poverty reduction and food security or for economic development. While economic development policies tend to emphasize large-scale agro-business to increase agricultural commodities production19, rural development programs continue to encourage small-scale agricultural holdings that are sometimes at odds with the goal to expand and intensify commercial production.

Related to agriculture and fishing

- Environment and natural resources

- Fishing, fisheries and aquaculture

- Economy and commerce

- Watersheds

References

- 1. International Rice Research Institute. “World Rice Statistics.” http://ricestat.irri.org:8080/wrsv3/entrypoint.htm Accessed 27 January 2019.

- 2. Statista.com 2019. “Paddy rice production worldwide in 2017 and 2018, by country (in million metric tons)”. https://www.statista.com/statistics/255937/leading-rice-producers-worldwide/ Accessed 27 January 2019.

- 3. Statista.com 2018. “Principal rice exporting countries worldwide in 2017/2018 (in 1,000 metric tons)”, https://www.statista.com/statistics/255947/top-rice-exporting-countries-worldwide-2011/ Accessed 27 January 2019.

- 4. Association of Natural Rubber Producing Countries 2018. ANRPC Releases Natural Rubber Trends & Statistics January 2018, 23 February 2018. http://www.anrpc.org/html/news-secretariat-details.aspx?ID=9&PID=39&NID=1776 Accessed 27 January 2019.

- 5. Financial Times 2010. “Rubber price breaks 58-year record” 1 April 2010. https://www.ft.com/content/636c534c-3ce1-11df-bbcf-00144feabdc0 Accessed 27 January 2019.

- 6. International Coffee Organization. “Total production by all exporting countries.” 2016. Accessed 11 March 2016. http://www.ico.org/prices/po-production.pdf

- 7. Hortle, K. G. 2007. Consumption and the Yield of Fish and Other Aquatic Animals from the Lower Mekong Basin. MRC Technical Paper No. 16. Vientiane: Mekong River Commission.

- 8. Mekong River Commission, 20 Years of Cooperation, Page 38. Accessed 3 June 2017. http://www.mrcmekong.org/assets/Publications/20th-year-MRC-2016-.pdf

- 9. Mekong River Commission, Catch & Culture Vol.21, No3. 5 Jan 2016. Accessed 3 June 2017. http://www.mrcmekong.org/news-and-events/newsletters/catch-and-culture-vol-21-no-3/

- 10. Rabobank. Rabobank World Seafood Trade Map 2015. Rabobank Industry Note #486. Accessed 3 June 2017. http://www.aquacircle.org/images/pdfdokumenter/efterret15/Rabobank_IN486_World_Seafood_Trade_Map_Nikolik_March2015.pdf

- 11. Ibid

- 12. Charoen Pokphand Foods PCL. “About Us.” Accessed 16 June 2015. http://www.cpfworldwide.com/en/about/.

- 13. Secretariat of the Rotterdam Convention. “Status of Ratifications.” Accessed 8 April 2015. http://www.pic.int/Countries/Statusofratifications/tabid/1072/language/en-US/Default.aspx#a-note-1.

- 14. Thapa, Ganesh and Raghav Gaiha. 2011. Smallholder Farming in Asia and the Pacific: Challenges and Opportunities. Rome: International Fund for Agricultural Development. Accessed 18 June 2015. http://www.ifad.org/events/agriculture/doc/papers/ganesh.pdf.

- 15. FAO. “Agricultural Development Economics: Smallholder Dataportrait.” Accessed 19 June 2015. http://www.fao.org/economic/esa/esa-activities/esa-smallholders/dataportrait/income-pluri-and-poverty/en/.

- 16. Prey Lang Community Network. 2015. Prey Lang Commune Research Report 2013-2014. Cambodia: Prey Lang Community Network. Accessed 18 June 2015. http://preylang.net/download/reports/PreyLang%20report%20English%20Version.pdf. View this on Open Development Datahub

- 17. FAO. “Asia and the Pacific’s Zero Hunger Challenge”. Accessed 3 June 2017. http://www.fao.org/asiapacific/perspectives/zero-hunger/en/

- 18. International Fund for Agricultural Development. “Laos: Southern Laos Food and Nutrition Security and Market Linkages Programme.” Accessed 16 June 2015. http://www.ifad.org/operations/pipeline/pi/laos_fnml.htm; “Farming First: Enhancing Sustainable Development Through Agriculture.” Accessed 16 June 2015. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/dsd/dsd_aofw_mg/mg_pdfs/mg_csd17_comm_posi.pdf.

- 19. World Health Organization. “Food Security.” Accessed 16 June 2015. http://www.who.int/trade/glossary/story028/en/