SDG 12 – “Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns” – has a monitoring framework of 11 targets and 13 indicators. Unmanaged consumption and production can contribute to depletion of natural resources.1 Sustainable consumption and production (SCP) requires a fundamental shift in the way we use services and products, including product lifecycle thinking. SCP means trying to “[do] more and better with less”2 – increasing quality of life while decreasing the impact of production on the environment due to pollution, waste and degradation.

SDG 12 covers use and management of natural resources (Target 12.2), as well as management of multiple types of waste, including food (12.3) and chemical waste (12.4). It also touches on shifting practices in waste generation (12.5) and public procurement (12.7). The goal encourages accountability through sustainability reporting (12.6). The means of implementation targets focus on international policy implementation (12.1), policy development (12.B), developing capacity (12.A) and financial support through restructuring economic incentives (12.C).

SDG 12, along with SDG 6 (Clean water), SDG 7 (Sustainable energy), SDG 11 (Sustainable cities and communities) and SDG 15 (Life on Land), will be reviewed at 2018’s High Level Political Forum.3 SDG 17 (Partnerships for the goals) is reviewed every year.

Context

Sustainable consumption and production has been part of the global development agenda since the UN Conference on Environment and Development in 1992, and was defined in 1994 at the Oslo Symposium. In 2012, heads of state at the UN Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20) adopted the 10-Year Framework of Programmes on Sustainable Consumption and Production Patterns (10YFP).4 This is a global framework for action to shift towards SCP and is closely connected to SDG 12 – indicator 12.1 refers explicitly to implementing it. The Asia-Pacific region has also developed a regionally-appropriate 10-year plan.

Because SCP reflects such a significant shift away from our current ‘take-make-dispose’ culture, systemic change is necessary. This requires shifting from a traditional model of economic growth to a ‘circular economy’ approach, which is based on three things:

- design out waste and pollution

- keep products and materials in use

- regenerate natural systems.5

Recycling and reusing resources, energy efficiency and value-chain optimization are all examples of how this shift can be implemented.6

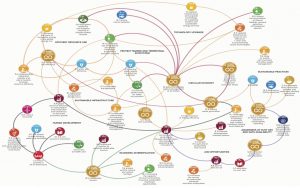

SDG 12 cannot be achieved without treating all the SDGs as interconnected. Given SDG 12’s connection with environmental impacts and economic growth, it is also connected to SDGs 6 (Clean Water), 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), 13 (Climate Change), 14 (Life below Water) and 15 (Life on Land), among others. The visualisation below indicates some of the interconnections between SDG 12 and the other SDGs.

SDG 12 is interlinked with many of the other SDGs. This map is not comprehensive and shows only some of the interlinkages. Source: UNESCAP. Accessed June 19, 2018.

A regional approach is necessary to effectively implement SDG 12, especially in the Asia-Pacific. Rapid economic growth, including in the Lower Mekong countries (LMCs), is expected to contribute to increased consumption globally. Debt-fuelled consumption is on the rise along with the region’s rapid development; consumer debt in Thailand is the highest in the LMCs and the Asia-Pacific region.7 While promoting household consumption is often an important part of national policies on economic growth and poverty alleviation, increased consumption also has significant environmental impacts.8 For the LMCs, where three of the five countries are least developed countries, policies need to address both continued economic development and poverty alleviation while ensuring environmental sustainability.

The importance of multilateral cooperation is recognized explicitly in Indicator 12.4.1 (Parties to and compliance with international multilateral environmental agreements).

Localisation and regionalisation

The Asia-Pacific region is considered a pioneer in SCP, where it began with the creation of the Asia Pacific Roundtable on SCP (APRSCP) in 1997. Its purpose is to increase access to information, collaborate with UNEP including to facilitate regional cooperation and provide expertise on SCP in the region.9 Recently, the APRSCP, alongside the EU’s SWITCH-Asia Programme and UNEP, developed an SCP Roadmap for the region. As a live document, the initial version was launched in 2014,10 with a revision developed for the years 2017–2018.11

Early acceptance of SCP has not translated into continued strong progress along this path in the Asia-Pacific region. Economic growth has been founded on unsustainable consumption and production patterns that make inequality and environmental degradation worse.12 Progress on SCP has gone backwards, and the region urgently needs to reverse material consumption and footprint trends to meet SDG 12, despite progress on individual targets.13 ESCAP’s regional road map for implementing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development does not explicitly mention SCP.14

Progress has been stagnant for SDG 12 in ASEAN.15 However, the importance of the concept is recognized by member countries and SCP is one of the five named priority areas for the ASEAN Vision 2025.16 ASEAN countries also issued a joint statement on the implementation of SCP in ASEAN in 2013.17 Policy-wise, all the LMCs have included sustainable consumption in at least one national level policy,18 while Cambodia and Thailand each have a clear governmental agency coordinating SCP.19 Vietnam mentions SCP in law.20 The LMCs are exploring SCP through schemes such as eco-labeling,21 reducing plastics,22 organic farming23 and ecotourism24.

Forest landscape in the Nam Ha National Protected Area in Lao PDR, which is an ecotourism destination. Photo by Rds26. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Waste reduction and management are particularly troublesome for Southeast Asia. The proportion of treated wastewater is low, while more plastic, hazardous and e-waste is being produced.25 Food waste is also a particular concern. In low-income countries in Southeast Asia where rice is the dominant crop, agricultural production and post-harvest handling and storage yield high food losses.26 It is estimated that 15–50 percent of fruits and vegetables and 12–30 percent of grains are lost between the producer and the consumer.27 Addressing waste issues is a key aspect of ASEAN’s Socio-Cultural Community Blueprint.28 ASEAN also created a Working Group on Chemicals and Wastes in 2015, which aims to strengthen regional coordination and cooperation to address chemical and waste-related issues, including those under relevant multilateral environmental agreements.29

Countries like Vietnam and Thailand have created national chemical inventories to improve chemical regulation, while Vietnam and Lao PDR have banned and are phasing out highly hazardous pesticides.30 Regional cooperation is necessary for the most effective chemical management to prevent multinational corporations from using chemicals in one country that might be prohibited in another.31

Additional efforts to harmonise standards across ASEAN, such as energy standards for appliances and technologies, can help to remove resource-inefficient products from the market.32 The ASEAN Economic Community is in a good position to support or carry out this type of work.

Means of implementation

Sustainable tourism (12.B) and fuel subsidies (12.C) are considered priorities in the Asia-Pacific region. Tourism is important in the LMCs, especially Cambodia and Thailand, and is forecast to grow.33 Good governance is needed to prevent biodiversity degradation, minimize pollution, and encourage sustainable resource consumption.34 Regarding 12.C, fossil fuels significantly impact climate change, and subsidies for their use support the production of cheap chemicals. Fossil fuel subsidies are extensive in in Asia, although subsidies have been lowered in a number of countries, including Thailand and Vietnam.35 Fossil fuel subsidies are of limited benefit for the poor, who lack electricity connections and vehicles,36 and are therefore in conflict with the 2030 Agenda approach of “leaving no-one behind”.

Policy coherence is necessary to accomplish SDG 12, and underlines the majority of the indicators for SDG 12.37 Because many physical and socioeconomic factors form the foundation for production and consumption patterns, policies need to go after the root causes of unsustainable consumption and production across the SDGs, particularly SDG 8 (Decent work and economic growth) and SDG 9 (Industry, innovation and infrastructure).38 With early action and the right policies, incentives and access to technology, developing economies such as Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar can encourage gains in resource efficiency.39

UNESCAP’s identified priorities for the region have a strong policy focus, unifying approaches using an integrated circular economy approach, developing a 10-year framework of programmes and encouraging corporate change.40 Other priorities are strengthening capacity building and financial support, encouraging stakeholder involvement and developing monitoring systems and indicators.41

Although research and development on relevant SCP technologies (SDG 12.A) is an important means of implementation, it does not feature as a priority in ASEAN or the Asia-Pacific.

Follow up and review, monitoring and evaluation

Nine of 13 SDG 12 indicators remain at Tier III. Global data are available for only Indicators 12.2.2 and 12.4.1.

| Indicator | Agency | Tier | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12.1.1 | UNEP | II | -- |

| 12.2.1 | UNEP | III | Initial review of the methodology is expected for June 2018; methodology is expected to be completed by 2020 |

| 12.2.2 | UNEP | I | -- |

| 12.3.1 | FAO, UNEP | III | The indicator is divided into two parts, a and b. Methodological work for 12.3.1a is expected by November 2018. Methodological work for 12.3.1b is more advanced. UNEP and FAO will work together to consolidate a and b together for one coherent indicator. |

| 12.4.1 | UNEP | I | -- |

| 12.4.2 | UNSD, UNEP | III | Although methodological work on this indicator was expected to be completed by mid-2018, at May 2018 this indicator remained at Tier III. |

| 12.5.1 | UNSD, UNEP | III | A conceptual framework is expected for June 2019. |

| 12.6.1 | UNEP, UNCTAD | III | Methodology was expected to be proposed by April 2018. However, as at May 2018 this indicator remains at Tier III. |

| 12.7.1 | UNEP | III | Methodological work was expected to be completed by December 2017 but at May 2018 this indicator remains at Tier III. |

| 12.8.1 | UNESCO-UIS | III | Methodological work is expected to be completed by 2017, then fine-tuned for the next data collection cycle in 2020. |

| 12.a.1 | Under discussion among agencies (OECD, UNEP, UNESCO-UIS, World Bank) | III | -- |

| 12.b.1 | UNWTO | III | The first version of methodological work is expected for June 2017. If this is not accepted additional work will be required, stretching beyond June 2017. |

| 12.c.1 | UNEP | III | A final methodology is expected to be proposed by March 2018. However as at May 2018 this indicator remains Tier III. |

Chart created by ODM June, 2018. CC BY SA 4.0. Data source Inter-Agency and Expert Group on SDG Indicators. 2018. Tier Classification for Global SDG Indicators 11 May 2018. Accessed June 19, 2018.

Regional data on SDG 12 are not available for the Asia-Pacific region.42 Country-level data for some countries are available for some of the indicators.

Indicators 12.2.1 and 12.2.2 are the same as for SDG 8.2.43 Relevant for 12.2.244 (and 8.2.2) is the System of Environmental-Economic Accounting, a global standard for producing internationally comparable statistics on the environment and its relationship with the economy. It has been identified and affirmed by the UN Statistical Commission as key to achieving the 2030 Agenda.45

Compliance on the Montreal Convention (12.4.1) is high for the LMCs at 100%, while compliance with the Basel and Rotterdam conventions is low for the LMCs. Thailand leads compliance in the region.

A variety of initiatives have been developed to support implementation of the goal. For sustainability reporting (12.6.1), the Global Reporting Initiative has developed a global sustainability reporting tracker, which is a database of voluntarily disclosed sustainability reports, and indicates which countries have sustainability reporting policies. This database indicates that only Thailand and Vietnam among LMCs have policies on sustainability reporting.46 Another online platform called the SCP Clearinghouse allows the global community working on implementing SDG 12.1 to connect and coordinate activities.47

References

- 1. ADB. 2017. Key Indicators for Asia and the Pacific 2017. Accessed May 28, 2018.

- 2. UNEP. 2010. The ABCs of SCP: Clarifying Concepts on Sustainable Consumption and Production. Accessed February 28, 2018.

- 3. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. HLPF 2018: Introduction. Accessed May 28, 2018.

- 4. UNEP. What is the 10YFP? Accessed June 4, 2018.

- 5. Ellen Macarthur Foundation. Circular Economy Overview. Accessed June 5, 2018.

- 6. UNCTAD. Circular Economy. Accessed June 5 2018.

- 7. S. Castro-Hallgren. 2017. Ch.3: Regional Policy Trends for Strengthening the Inclusion of Sustainable Consumption and Production (SCP) in Public Governance in Regional Policy Trends for Strengthening. Accessed June 4, 2018.

- 8. Ibid.

- 9. Asia Pacific Roundtable for Sustainable Consumption and Production. APRSCP Thematic Projects and Initiatives. Accessed June 4, 2018.

- 10. 10YFP, UNEP, SWITCH-Asia. 2014. Roadmap for the 10YFP Implementation in Asia and the Pacific 2014-2015. Accessed June 4, 2018.

- 11. UNEP. About Roadmap. Accessed June 4, 2018.

- 12. UNESCAP. 2018. SDG 12 Goal Profile. http://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/SDG%2012%20Goal%20Profile.pdf. Accessed May 28, 2018.

- 13. Ibid.

- 14. UNESCAP. 2017. Regional Road Map for Implementing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in Asia and the Pacific. Accessed June 5, 2018.

- 15. UNESCAP. 2017. ASEAN SDG Baseline. http://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/publications/ASEAN_SDG_Baseline_0.pdf. Accessed May 28, 2018.

- 16. ASEAN. 2015. ASEAN Community Vision 2025. Accessed June 6, 2018.

- 17. ASEAN. 2013. Joint Statement On The Implementation Of Sustainable Consumption And Production In Asean By The Asean Ministers Responsible For Environment. Accessed February 28, 2018.

- 18. Corresponding with Indicator 12.1.1. Cambodia: National Policy on Green Growth, National Strategic Plan on Green Growth 2013-2030; Lao: National Socio-Economic Development Plan (2011-2015), the National Policy On Sustainable Hydropower Development; Viet Nam: National Strategy of Green Growth, National Action Plan on Green Growth (2014-2020), Vietnam’s Socio-economic Development Strategy For The Period Of 2011-2020, National Action Plan for the Implementation of the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda; Myanmar: Myanmar Agenda 21 (1997), National Sustainable Development Strategy 2009; Thailand: 20 year National Strategy 2017-2036 includes Green Growth as a pillar.

- 19. In Cambodia, it is a Technical Working Group under the National Council for Sustainable Development (Department of Climate Change: General Secretariat of the National Council for Sustainable Development. NCSD Structure, National Council of Sustainable Development General Secretariat. Press Release No. 003, August 31 2016. Accessed February 19, 2018), and in Thailand, the National Committee for Sustainable Development. Accessed February 19, 2018.

- 20. Law on Environmental Protection 2014. Accessed February 19, 2018.

- 21. Green Label: Thailand. 2013. A Guide to Thai Green Label Scheme. Accessed February 28, 2018.

- 22. Bun and Associates. 2018. Legal Update Alert: Management of Plastic Bags in Cambodia. Accessed February 28, 2018.

- 23. Public Relations Department (Thailand). New Strategy to Develop National Organic Agriculture. April 19 2017. Accessed February 19, 2018.

- 24. Ecotourism Laos. Accessed February 19, 2018.

- 25. UNESCAP. 2018. SDG 12 Goal Profile. http://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/SDG%2012%20Goal%20Profile.pdf. Accessed May 28, 2018.

- 26. UNESCAP. 2017. Sustainable management of natural resources in Asia and the Pacific: trends, challenges and opportunities in resource efficiency and policy perspectives. Note by the secretariat, Ministerial Conference on Environment and Development in Asia and the Pacific, E/ESCAP/MCED(7)/2. http://apministerialenv.org/document/MCED_2E.pdf. Accessed June 13, 2018.

- 27. Save Food Asia-Pacific. 2018. What is Food Loss and Food Waste. Accessed June 13, 2018.

- 28. ASEAN. ASEAN Cooperation on Chemicals and Waste. Accessed June 4, 2018.

- 29. Ibid.

- 30. UNESCAP. 2018. SDG 12 Goal Profile. http://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/SDG%2012%20Goal%20Profile.pdf. Accessed May 28, 2018.

- 31. UN, ADB, UNDP. 2017. Asia-Pacific Sustainable Development Goals Outlook. Accessed June 4, 2018.

- 32. S. Castro-Hallgren. Regional Policy Trends for Strengthening the Inclusion of Sustainable Consumption and Production. Accessed June 4, 2018.

- 33. UNESCAP. 2017. SDG 12 Goal Profile. http://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/SDG%2012%20Goal%20Profile.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2018.

- 34. Ibid.

- 35. ADB. 2016. Fossil Fuel Subsidies in Asia: Trends, Impacts, and Reforms – Integrative Report. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/182255/fossil-fuel-subsidies-asia.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2018.

- 36. Ibid.

- 37. UN, ADB, UNDP. 2017. Asia-Pacific Sustainable Development Goals Outlook. Accessed June 4, 2018.

- 38. Ibid.

- 39. Ibid.

- 40. UNESCAP. 2017. SDG 12 Goal Profile. http://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/SDG%2012%20Goal%20Profile.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2018.

- 41. Ibid.

- 42. APFSD. 2018. Asia-Pacific SDG Data Availability Report. https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/APFSD5_INF2E.pdf. Accessed May 28, 2018.

- 43. UNSD. Sustainable Development Goal 8. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg8. Accessed June 6, 2018.

- 44. UNEP. 2018. Metadata Indicator 12.2.2. Accessed June 4, 2018.

- 45. United Nations Statistical Commission. 2018. Report of the Committee of Experts on Environmental-Economic Accounting: Note by the Secretary-General. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/statcom/49th-session/documents/2018-11-EnvironmentalAccounting-E.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2018.

- 46. GRI. 2018. SDG Target 12.6 – Global Tracker. Accessed June 4, 2018.

- 47. One Planet. What is SCP? Accessed June 4, 2018.