Introduction

Water is the lifeblood of the Lower Mekong Countries. With economies and cultures inextricably connected to the Mekong River, built as they are on the production and consumption of rice and fish, people living in the Mekong countries are highly sensitive to changes in water. This is especially so for countries lying downstream of the Mekong River system and making up the river’s delta, Cambodia and southern Vietnam.

Villagers of Sre Kor village, Se San District, Steung Treng Province, Cambodia use the Se San River as one of the main routes for daily livelihoods activity. Photo by WorldFish via Flickr. Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Water resources include freshwater and saltwater. Sometimes water resources is defined as freshwater resources only, which is water that collects on or under the earth’s surface as part of the water cycle.1 Freshwater can be found as surface water in rivers and lakes, and in the ground as groundwater. For the so-called Lower Mekong Countries, their dependence on freshwater found in the Mekong River is significant. However, saltwater resources, in the form of marine and coastal areas, are also an important resource for four of the five Lower Mekong countries (with the exception of land-locked Laos), supporting fisheries, tourism, and local livelihoods.

Data quality and completeness on water resources in the region varies, with the Mekong River Commission and the FAO being the primary organizations managing and producing relevant data.

Freshwater Sources

The water cycle is core to the production of freshwater. At its most basic, the water cycle starts with evaporation of water from the earth’s surface, which collects into clouds, then falls back to the earth as rain or snow. 2 This freshwater collects in rivers and lakes, and gets absorbed into natural aquifers, or underground layers of rock that collect water.

Water is a finite resource. The same water continuously circulates around the planet in what is known as the water cycle. But it’s not just about supply–how much water there is and how clean it is. Water resources management is about a host of issues such as government policy, financing, allocation, transboundary conflict, and the ecosystem. Image by Global Water Partnership via Flickr. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Freshwater resources are renewable, but this does not mean more water can be made – the amount that is available is finite.3 Furthermore, there are large variations in the location of freshwater resources even while freshwater is essential for human survival, exacerbated by increasingly unsustainable water use and climate change. One attempt to capture the complexities of the demands on freshwater resources is through the concept of water security, which the UN defines as “the capacity of a population to safeguard sustainable access to adequate quantities of acceptable quality water for sustaining livelihoods, human well-being, and socio-economic development, for ensuring protection against water-borne pollution and water-related disasters, and for preserving ecosystems in a climate of peace and political stability.”4

The fact that the water is a transboundary resource, spanning the six national borders of China, Myanmar, Thailand, Lao PDR, Cambodia, and Vietnam, complicates access. As each country has individual and unique agendas, competition for water will increase between countries. Those who are upstream – China – gain a geographical advantage in exploitation of the resources of the Mekong River, while those who are downstream – Cambodia and Vietnam – face growing difficulties in protecting ecological functions on the southern end of the river that are crucial for the flow of the entire river. Read more about the unique aspects of the Mekong River here, and see more on the other rivers and lakes in the Mekong Region here.

There are concerns about water security in the Lower Mekong Region, given heavy demands on the Mekong River, and the transboundary and cumulative effects of these demands. These demands include industrial fisheries and aquaculture for export as well as small-scale fisheries for livelihoods; other industrial uses such as agriculture, extractives, tourism, and others; energy, especially hydropower; and urban use.

Aqueduct atlas map created by ODM. View more water datasets on Map Explorer.

Water policy and administration

Because of the transborder nature of water ecosystems, a regional approach to water governance and the management of water resources is fundamental to both sustainable development and the assurance of water rights. The Mekong River Commission has served as a venue for countries to discuss Mekong-related water issues but there is still little in the way of a regional governance framework to mediate its management and use. Read more about what this means in the Lower Mekong Region here.

Water rights

Water rights can refer to both the legal frameworks defining access to and the management of water, as well as the human right to water and sanitation. While these ideas are connected they are separate concepts. Read more about what water rights means in the context of the Lower Mekong Region here.

Differential impacts

Water security impacts vulnerable populations more, with multiple vulnerabilities causing a cumulative impact. For example, while both men and women use water resources, women are usually responsible for collecting water for their families, meaning that any changes in water resources impacts them first.5 Furthermore, women have unique needs related to water during menstruation, pregnancy, childbirth and childrearing, so any changes to water resources impacts them more.6 In another example, indigenous peoples have a unique knowledge of water management not only for their livelihoods but also in line with their cultural practices, so changes to water resources impact not only their livelihoods but also their culture.7 Yet these groups continue to be excluded from both decision-making and the data that supports the determination of how water resources will be shared, used, and managed. Read more about how inclusive policy, data collection, and other practices can play a role to include vulnerable populations here.

Women along the Mekong Delta. Photo by @allpointseast. Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Demands

There are many conflicting demands on water resources in the region, all of which demand more water. Although each individual demand can be justified, when looking at all demands together it is clear that the current finite water resources cannot sustain the demands on it indefinitely. The impacts of climate change are expected to increase water insecurity.8 Below is a very brief discussion of a few of the most relevant demands.

Fishing, fisheries and aquaculture

Fisheries are a vital part of the regional economy, with more than two-thirds of the population involved in the industry. The sector, including aquaculture, was estimated most recently in 2015 to generate as much as USD 17 billion per year, contributing three percent to the combined GDP of Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand (up to 12 percent for Cambodia), representing 13 percent of the world’s total value for fisheries9, and 18 percent of the world’s freshwater fish catch10. However, it is important to note that data on this industry is limited and thus its contribution is likely to be underreported.11

However, the sustainability of the region’s fishing industry is dependent on the health of the water ecosystem, which is negatively impacted by other demands such as hydropower energy, agriculture, and urbanization. One key marker of this is that both fish capture and fish diversity in the Lower Mekong Basin are in decline.12 Read more about the Mekong River here.

Agriculture and other industries

The expansion of agro-industry throughout the region has been a significant part of country strategies for economic growth. However such expansion is largely dependent on increasing and improving irrigation, even though irrigated agriculture already uses the most water in the region.

To see more about the SDG framework and clean water, click here. To see more about the SDG framework and aquatic ecosystems, see here. A dataset on the SDGs, indicators, and related links, is available here.

Given the push toward agro-industry, water extraction for irrigated agriculture is anticipated to continue to increase.

Agriculture not only places demands on water through use, but also potentially pollutes water. Algal blooms, caused by fertilizer run-off and exacerbated by climate, choke fish and poison water. These blooms are present in the Mekong13 and Vietnam’s coastal areas.14 The same issues regarding use and pollution are present for other key industries in the region, such as manufacturing and processing, extractives, and tourism.15

While no Mekong Basin-wide study of pollution has yet been undertaken, a study aggregating the results of localized monitoring and research efforts identified pollution hotspots on the Mekong.16

Energy

With a growing population and a push to reach 100% electrification, water is seen as a critical resource for meeting energy needs through hydropower development. CGIAR’s Water, Land and Ecosystems (WLE) program has documented 805 dams, including 44 under construction.17

While dams associated with the Lower Mekong Basin may generate as much as 30,000 MW of energy, the impacts on the region’s hydrology and biodiversity, thus impacting fisheries and agriculture, will also be significant.18 Read more about hydropower development here.

Cities and a growing population

With more people moving to cities, there is more demand for water, and access to water is changing. Demands include access to clean water, sanitation and hygiene services. An increase in urbanization in the region, and the expectation that this trend will continue, means a growing stress on water resources.

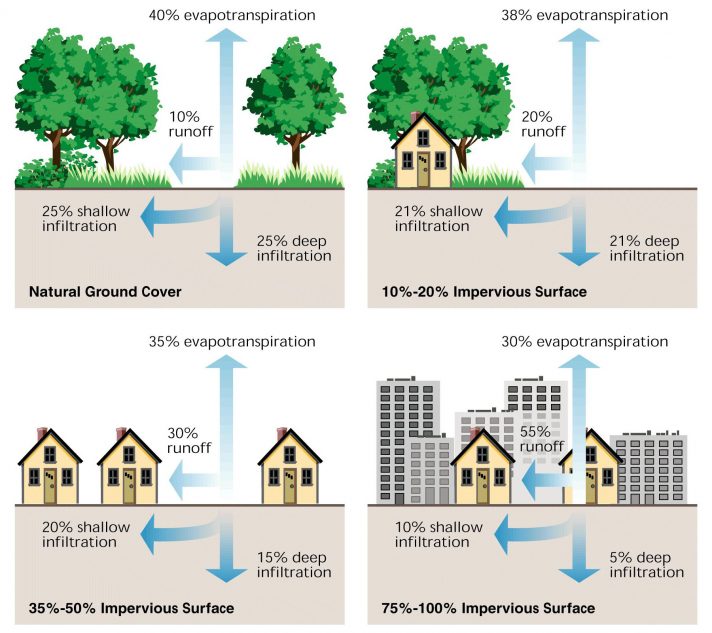

Cities, with their hard surfaces, also disrupt the water cycle by blocking the absorption of rainwater into the soil. This limits the ability of water to collect in aquifers and increases surface water run-off into rivers and lakes. However, the common practice of filling in lakes and wetlands to create new land for development means that water is no longer able to drain into these areas.

Relationship between impervious cover and surface runoff. Impervious cover in a watershed results in increased surface runoff. As little as 10 percent impervious cover in a watershed can result in stream degradation. From “Stream Corridor Restoration: Principles, Processes, and Practices“. Federal Interagency Stream Restoration Working Group, 1998; “U.S. Department of Agriculture”.

References

- 1. J-M. Faurès. 1997. Indicators for sustainable water resources development. Accessed March 23, 2020.

- 2. NASA. The Water Cycle. Accessed March 23, 2020.

- 3. Global Water Partnership. 2017. The Water Challenge. Accessed March 23, 2020.

- 4. UN-WATER. 2013. What is water security? Infographic. Accessed March 19, 2020.

- 5. UN-WATER. Water and gender.Accessed March 20,2020.

- 6. Ibid.

- 7. Rutgerd Boelens, Moe Chiba, Douglas Nakashima and Vanessa Retana. 2006. Water and indigenous peoples. Accessed March 23, 2020.

- 8. IPCC. 2014. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- 9. So Nam, Souvanny Phommakone, Ly Vuthy, Theerawat Samphawamana, Nguyen Hai Son, Malasri Khumsri, Ngor Peng Bun, Kong Sovanara, Peter Degen and Peter Starr. 2015. Catch and Culture Volume 21,3. Accessed March 23, 2020.

- 10. Eric Baran, Eric Guerin and Joshua Nasielski. 2015. “Fish, sediment and dams in the Mekong.” Accessed March 23, 2020.

- 11. Chelsie L. Romulo, Zeenatul Basher, Abigail J. Lynch, Yu-Chun Kao & William W. Taylor. 2017. Assessing the global distribution of river fisheries harvest: a systematic map protocol. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- 12. So Nam, Souvanny Phommakone, Ly Vuthy, Theerawat Samphawamana, Nguyen Hai Son, Malasri Khumsri, Ngor Peng Bun, Kong Sovanara, Peter Degen and Peter Starr. 2015. Catch and Culture Volume 21,3. Accessed March 23, 2020.

- 13. Mart Stewart, Peter Coclanis. 2011. Environmental change and agricultural sustainability in the Mekong Delta, page 314. Accessed March 23, 2020.

- 14. Tran Van Dien and Pham Ngoc Hai. 2005. Monitoring algal bloom in Vietnam waters from ocean color satellite data. Accessed March 23, 2020.

- 15. An Giang. 2016. Fish kill blamed on pollution. Accessed September 2016. Other fish kills, associated with industrial waste and other pollution, have been reported on the Sre Pok, Dong Nai, Chaopraya, Tonle Sap and Red rivers as well as the Taungthaman Lake in Myanmar and canals in Ho Chi Minh City. In 2016, a massive fish kill along 215 kilometers of Vietnam’s central coast, associated with wastewater contamination, led to massive economic losses and sparked nationwide protests. Shannon Tiezzi. 2016. “It’s official: Formosa subsidiary caused mass fish deaths in Vietnam.” Accessed September 2016.

- 16. Ratha Chea, Gaël Grenouillet and Sovan Lek. 2016. Evidence of water quality degradation in Lower Mekong Basin revealed by self-organizing map. Accessed March 23, 2020.

- 17. CGIAR, Water Land and Ecosystems. Greater Mekong Dams Observatory. Accessed March 23, 2020.

- 18. Jory Hecht and Guillaume Lacombe. April 2014. State of Knowledge 5: The effects of hydropower dams on the hydrology of the Mekong Basin. Accessed March 23, 2020.