Extractive industries are the businesses that take raw materials, including oil, coal, gold, iron, copper and other minerals, from the earth. The industrial processes for extracting minerals include drilling and pumping, quarrying, and mining. Extractive industries are generally divided into two sectors: mining, and oil and gas.

An oil drilling platform near Phuket, Thailand. Photo by Vidar Lokken, 2011, Wikimiedia Commons. Taken 4 September 2011. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Mineral resources

The Lower Mekong countries are rich in mineral resources. The region has proven reserves of approximately 1.2 billion cubic meters of natural gas, 0.82 billion tons of oil, and 28.0 billion tons of coal. Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam possess large natural gas deposits, while Cambodia is getting closer to producing its own oil and gold.

Within the region, Thailand and Laos possess the greatest coal deposits and Vietnam has the largest oil reserves.1 (Vietnam has the third largest crude oil reserves in Asia after China and India.)2 Other mineral resources in the Lower Mekong—in addition to the energy-related commodities above—include gold, copper, jade, lead, zinc, phosphate, potash and gemstones, including rubies and sapphires.3 Myanmar, which is mostly outside the river basin, is endowed with substantial quantities of copper, nickel, zinc, manganese, and tin as well gemstones ruby, sapphire and jade.4

Minerals extracted

Mineral extraction is a key sector for driving economic development as reflected in ASEAN Minerals Cooperation Action Plan (AMCAP-III). AMCAP 2016–2025 aims to: “Create a vibrant and competitive ASEAN mineral sector for the well-being of the ASEAN people through enhancing trade and investment and strengthening cooperation and capacity for sustainable mineral development in the region.”5

Extractive industries are at varying levels of development across the five Lower Mekong countries, with Cambodia having progressed the least. The other four countries contribute significant amounts to the world’s production of two or more metals or minerals. Vietnam, Myanmar and Thailand also produce crude petroleum. Vietnam leads in production of crude oil, Thailand in natural gas. Cambodia is currently only recognized for its salt production, a mineral also produced in all of the other Mekong countries.

Thailand and Vietnam have the most developed extractive industries. Myanmar’s, which until recently was dominated by military-owned companies, has been opening up to private investment since at least 1988, and between 2001 and 2012 was one of the few sectors to see substantial Foreign Direct Investment (FDI.)6 Despite sanctions against Myanmar, international oil companies, such as Total SA, PTTEP and Chevron were active in the country between 1997 and 2012. 7

One of the largest extractive industries in the region may be significantly underreported: the production of jade in Myanmar. A 2015 report by the international NGO Global Witness stated that: “Until now the jade sector’s worth has been almost impossible to determine. However, based on new research and analysis, Global Witness estimates that the value of official jade production in 2014 alone was well over the US$12 billion indicated by Chinese import data…”8

Cambodia, while possessing oil reserves and various metals, including gold, has seen relatively little Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in the extractive sector, due largely to a lack of infrastructure.9

The Lower Mekong countries were among the top ten world producers by quantity for a number of minerals in 2016:

- Vietnam was the number two world producer of tungsten and bismuth, 4th for fluorspar and 9th for tin.

- Thailand was 4th for gypsum and 7th for feldspar.

- Myanmar was 2nd for tin and 7th equal for antimony.

- Laos was 11th for antimony and 18th for copper.10

Managing mineral wealth

Activities related to mining, oil and natural gas have been controversial throughout the Lower Mekong, as elsewhere. They often bring corporate interests into conflict with farmers and introduce risks of spills, pollution and deforestation that can have long-term consequences on the environment. Yet, in many cases, there has been a close relationship between development of oil and gas industries and a nation’s own energy needs and economic output. For instance, Vietnam and Thailand have both subsidized their oil industries, thereby keeping energy prices in their countries low. Vietnamese oil production is slowing as its fields mature – 2016 production of 320,000 barrels per day was 9% lower than the 2015 figure.11 Vietnam is a net exporter of crude oil but a net importer of oil products. In 2014, Thailand produced 42.1 billion cubic metres (bcm) of natural gas but consumed more (52.7 bcm, making it the 11th largest consumer of natural gas in the world). It relied on imported natural gas to make up the difference.12

Extractive industries, by their nature and conduct, are often incompatible with traditional land uses and risk harm to existing ecosystems. Extractive industries are often particularly problematic for indigenous peoples; the destruction of their livelihoods, community structures and culture by mining and other projects has been termed by some observers as ‘development aggression’.13

Tĩnh Túc Tin Mine, Cao Bằng, Vietnam. Photo by Gavin White, Flickr. Taken 4 May 2007. Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Generic.

Environmental impact assessments (EIAs) are a critical safeguard in protecting the landscape from the adverse effects of extractive activities. Questions have been raised regarding the efficacy of current EIA regimens in the region and the five countries are acting to improve these.14 Since 2011, Cambodia has been preparing a revision to its EIA law.15 Responsible companies also commit to plans to rehabilitate mining sites at the end of extraction.

The management and allocation of the large revenues generated from fossil fuel and other extractive industries can also lead to controversy. As the International Monetary Fund has noted, in developing countries resource riches, especially oil, present “very large, quickly growing, but time-limited production and revenue flows, combined with a high degree of volatility because of fluctuating world prices.” 16 They go on to observe that this provides a circumstance where weak administration, inefficient policies, and “outright corruption” can lead to the misallocation of national resource wealth. Around the world, this situation is termed the ‘resource revenue curse.’

Fluctuating commodity prices have hit some Lower Mekong countries hard. While Thailand and Vietnam’s mineral production by weight changed only a little between 2014 and 2015, for example, falling commodity prices led to large falls in revenue. The dollar value of Thailand’s 2015 production was over USD$6 billion less than 2014; for Vietnam the fall was USD$7 billion.17

Governance is a crosscutting issue in the region. None of the five Lower Mekong countries rank in the top ‘cleanest’ 100 of 176 countries in Transparency International’s 2016 Corruption Perception Index.18 Thailand had the best position, ranked at 101; Vietnam was 113, Laos 123, Myanmar 136 and Cambodia 156.

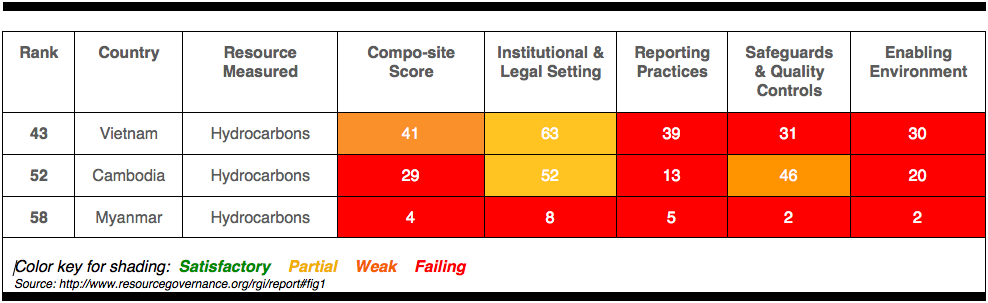

An indicator more closely associated with resource management is the Natural Resource Governance Institute’s Resource Governance Index (RGI), which scores and ranks countries with production in the oil, gas and mining sector on associated management policies and practices. The table below reflects the results of the 2013 RGI with respect to three of the five Lower Mekong countries; only Cambodia, Myanmar and Vietnam were assessed. The ranking is out of a pool of fifty-eight (58) countries, where 1 is best. The scores for institutional and legal setting, reporting practices, safeguards and quality controls, and enabling environment are out of a possible 100.19

Resource governance rankings for Vietnam, Cambodia and Myanmar (2013)

Despite its placing last in the 2013 RGI, Myanmar is now taking steps toward extractive industry transparency. The country has officially joined the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI), which requires extensive disclosure and measures to improve accountability in how production of oil, gas and minerals is governed.20 The first EITI report on Myanmar, published in December 2015, only covered part of the sector, but nevertheless contained useful information. It made a number of recommendations, including much greater disclosure from the two big military holding companies, UMEHL and MEC, that have a significant role in the country’s economy.21 Myanmar is yet to be assessed against the 2016 standard. In 2016, Vietnam’s Chamber of Commerce and Industry urged that country to participate in EITI.22

Civil society organizations across ASEAN collaborated with the Institute for Essential Service Reform (IESR) in 2014 to support the development of The framework for extractive industries governance in ASEAN,23 which advances four principles for good management in the sector: (1) Protection of the environment; (2) Respect and protect human rights; (3) Transparent and accountable practices; and (4) Sound Fiscal framework and revenue management.24

Related to extractive industries

References

- 1. Asian Development Bank. 2012. The Greater Mekong Subregion Power Trade and Interconnection: 2 Decades of Cooperation. Manila: ADB. Accessed 21 July 2015. http://adb.org/sites/default/files/pub/2012/gms-power-trade-interconnection.pdf. View on Open Development Datahub

- 2. U.S. Energy Information Agency 2017. https://www.eia.gov/beta/international/analysis.cfm?iso=VNM Accessed 7 May 2017.

- 3. Mekong River Commission. “Natural Resources.” Accessed 21 June 2015. http://www.mrcmekong.org/mekong-basin/natural-resources/.

- 4. Fong-Sam, Yolanda. 2012. “The Mineral Industry of Burma.” In 2012 Minerals Yearbook, Burma, Advance Release, 6.1-6.6. United States: United States Geological Survey. Accessed 21 July 2015. http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/country/2012/myb3-2012-bm.pdf.

- 5. http://www.asean.org/storage/2015/12/AMEM/AMCAP-III-(2016-2025)-Phase-1-(Final)2.pdf Accessed 7 May 2017.

- 6. Bissinger, Jared. 2012. “Foreign Investment in Myanmar: a Resource Boom but a Development Bust?” Contemporary Southeast Asia 34(1): 23–52, 30. Accessed 21 June 2015. http://www.academia.edu/1534773/Foreign_investment_in_Myanmar.

- 7. Offshoretechnology.com. 2012. “Spotlight: Myanmar’s controversial oil and gas industry.” Accessed 21 June 2015. http://www.offshore-technology.com/features/featurespotlight-myanmar-controversial-oil-gas-industry-abuse/.

- 8. Global Witness 2015. Jade: Myanmar’s Big State Secret. https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/oil-gas-and-mining/myanmarjade/ Accessed 7 May 2017

- 9. Soto-Viruet, Yadira and Yolanda Fong-Sam. 2011. “2011 Minerals Yearbook: the Mineral Industry of Cambodia.” In 2011 Minerals Handbook, Cambodia, Advance Release, edited by United States Geological Survey, 8.1-8.4. Accessed 21 June 2014. http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/country/2011/myb3-2011-cb.pdf.

- 10. World Mining Congress. 2018 “World Mining Data. Volume 33: Minerals production, 2018.” Accessed 31 August 2018. http://www.wmc.org.pl/sites/default/files/WMD2018.pdf

- 11. US Energy Information Administration, 2017. https://www.eia.gov/beta/international/analysis.cfm?iso=VNM Accessed 7 May 2017.

- 12. World Energy Council 2017. https://www.worldenergy.org/data/resources/country/thailand/gas/ Accessed 7 May 2017.

- 13. The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Persons (UNDRIP) requires “free, prior and informed consent” from indigenous peoples, as well as fair compensation, before they can be relocated from their land. All five Lower Mekong nations supported adoption of the UNDRIP.

- 14. Rodolfo Stavenhagen cited in Anongos, Abigail, Dmitry Berezhkov, Sarimin J. Boengkih, Julie Cavanaugh-Bill, Asier Martínez de Bringas, Robert Goodland, Stuart Kirsch, Roger Moody, Geoff Nettleton, Legborsi Saro Pyagbara and Brian Wyatt. 2012. Pitfalls and Pipelines, Indigenous Peoples and Extractive Industries. Philippines, Denmark, London: Tebtebba Foundation, International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, Indigenous Peoples Links, 3. Accessed 22 June 2015. http://www.iwgia.org/iwgia_files_publications_files/0596_Pitfalls_and_Pipelines__Indigenous_peoples_and_extractive_industries.pdf.

- 15. “The UN Declaration was adopted in 2007 by a majority of 143 states in favour, 4 votes against (Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States) and 11 abstentions (Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Burundi, Colombia, Georgia, Kenya, Nigeria, Russian Federation, Samoa and Ukraine).” United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. 2007. “Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.” Accessed 22 June 2015. http://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/IPeoples/Pages/Declaration.aspx.

- 16. USAID. 2015. “Mekong Governments, Civil Society, Reach Agreement on Environmental Impact Assessment Agenda.” Accessed 22 June 2015. http://www.usaid.gov/asia-regional/press-releases/may-15-2015-mekong-governments-civil-society-reach-agreement.

- 17. C. Reichl, M. Schatz, G. Zsak. Op cit.

- 18. Transparency International 2016. http://www.transparency.org/news/feature/corruption_perceptions_index_2016#table Accessed 7 May 2017.

- 19. 2013 Resource Governance Index https://resourcegovernance.org/sites/default/files/rgi_2013-compscores.pdf Accessed 12 May 2017. Also see International Monetary Fund. 2012. Guide on Resource Revenue Transparency. Washington DC: IMF, 2. Accessed 21 June 2012. https://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/2007/eng/101907g.pdf.

- 20. Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative 2017. https://eiti.org/countries Accessed 7 May 2017.

- 21. https://mdricesd.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/meiti-first-report-2013-2014-jan-2016.pdf Accessed 9 May 2017.

- 22. Viet Nam News 2016. “VN urged to join EITI for mining transparency” August 22 2016. http://vietnamnews.vn/economy/301512/vn-urged-to-join-eiti-for-mining-transparency.html#Uo6fBkMMuiZI3Ou1.97 Accessed 7 May 2017

- 23. Institute for Essential Services Reform. 2014. The Framework for Extractive Industries Governance in ASEAN, First Edition. Jakarta: IESR. Accessed 22 June 2015. http://www.resourcegovernance.org/sites/default/files/FrameworkExtractiveIndustriesGov_20141202.pdf. View on Open Development Datahub

- 24. PanNature. 2014. “Launching ‘The framework for extractive industries governance in ASEAN.’” Accessed 22 June 2015. http://www.nature.org.vn/en/2014/12/launching-the-framework-for-extractive-industries-governance-in-asean/.